This post by Jeremy Symons was originally published on LinkedIn Pulse.

It was an unexpectedly tense moment among Republicans on the floor of the United States Senate. The Senate was voting on the repeal of a regulation designed to reduce methane pollution from the oil and gas industry. The rule was a key element of former President Obama’s climate change plan, and the vote was the GOP-controlled Senate’s first attempt at rolling back Obama’s environmental legacy since President Trump took office. Lobbyists had assembled a long list of environmental rollbacks for Congress to deliver to the new president. The congressional guillotine was about to claim its first head from that list.

John McCain was heading to cast his vote when he was intercepted by his friend, Senator Barrasso, a fellow Republican. Barrasso physically planted himself between McCain and the voting table.

In a matter of seconds, McCain was surrounded by a circle of Republican Senators who were executing their intervention plot, following instructions from GOP leadership.

Three tense minutes of debate ensued, with Senators pressing McCain. Vice President Pence, on hand to cast a tie-breaking vote, had already visited McCain on behalf of the White House. Pence, still waiting in the Senate wings, would only be needed if McCain could be persuaded to change his vote.

John Cornyn, the Republican Whip responsible for enforcing party discipline on votes, loomed over the shorter McCain, arms crossed, face menacing, like a bouncer at the party gates. McCain at times stabbed with his hands in his characteristically animated manner when he goes on the offensive, adding exclamation points to his arguments.

Finally, John McCain brushed his colleagues aside, called for the attention of the Senate clerk, and jammed his thumb down, handing Cornyn and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell their first defeat on any vote since President Trump took office. It was a rare and surprising defeat – the first time any Senate leader had lost such a vote in more than five years. Vice President Pence headed back to his motorcade, his trip wasted.

After a long and controversial absence, the climate maverick was back.

Maverick McCain Re-Emerges on

Methane Vote: Surprise vote sinks

resolution (CQ Roll Call)

…“One person surprised

everybody,” Oklahoma GOP Sen. James M.

Inhofe, a senior Environment and Public

Works Committee member, said of McCain’s

vote against the CRA. “I was very certain the

votes were there because we wouldn’t bring it

up if the votes weren’t there.”…

When asked if there was pressure to change

his vote, McCain said, “Of course.” When asked

if it had any effect, McCain said, “I voted.”

McCain’s Climate Legacy: No Easy Labels

Climate change is often cited by journalists as part of McCain’s legacy of bucking his own party. A number of climate writers have also reflected on McCain’s climate legacy as the nation mourns. Some are full of praise. Eric Holthaus at Grist names McCain “an American climate hero.”

Others are less kind. Kate Sheppard at HuffPost writes: “McCain was arguably the reason we don’t have a sane climate law in place right now.”

VOX’s self-identified “climate hawk” David Roberts tweeted out a storm of protest against the frequent lionizing of McCain’s climate record, including these snippets:

“The net result of all McCain’s supposed

climate heroism? Nothing. Tons & tons of

atmospherics, tons of worshipful interviews,

tons of drippy tributes, but no legislation, no

policy, no reductions in GHGs…

the fact is, McCain was a “maverick” when it

brought him approbation & attention…but

never in the face of real political risk.”

The disparity between these views drives me, as a long-time advocate for climate action, to share this more in-depth look at McCain’s climate legacy.

I start from the premise that McCain’s complicated history on climate defies my ability to provide summary judgement. This is a personal perspective that includes my experiences and lessons learned from observing, meeting, sometimes following, and sometimes failing to persuade John McCain.

McCain often shared his most innermost thinking on climate politics when I was in the company of the powerful mother-daughter team of Roberta and Michele Combs. Roberta, President and CEO of the Christian Coalition of America, and Michele, Founder and President of Young Conservatives for Energy Reform, were steadfast and influential supporters of McCain’s leadership on climate change, from the early fights in Congress to the presidential campaign trail in 2008 and beyond.

I have dedicated too much of my life’s work fighting for climate action to not have a biased perspective. I embrace that by trying to shed light and expose my perspective and reasoning, rather than hide it. I do strive, however, to be true to the facts and complete in the telling as I know it. Importantly, I aim to isolate my retelling and views strictly to climate change, without the goggles of partisanship, that, considering his wide-ranging political career and candidacy for president, will inevitably tinge how most any reader will view his climate legacy.

What are my biases? I was a strong supporter of McCain and Lieberman’s campaign for climate action, working at National Wildlife Federation, in the U.S. Senate, and for the past five years at Environmental Defense Fund. Suspend your concerns, however, that I will only share one side of McCain’s climate legacy. As someone who followed McCain when he was at his climate best, I am keenly aware of when he was not, and I share those memories and lessons as well. (In the picture, from left to right: me, McCain, Larry Schweiger, and Adam Kolton, presenting a National Wildlife Federation award in 2004).

Before we get to either those highs or lows, however, we need to recall the Senator who simply wanted some answers.

The Searcher for Truth: 2000-2001

McCain first caught my interest from a climate change perspective in May 2000 as I reviewed a congressional schedule as part of my work at the Environmental Protection Agency. Surprisingly, McCain had called for a climate change hearing in the Senate’s Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, which he chaired.

I was worried. The context on Capitol Hill was not promising. More than two years had passed since Al Gore had helped secure a global climate agreement in Kyoto, Japan that many in Congress loved to vilify. Was McCain planning to use his committee to pile on to these attacks in the final year of the Clinton-Gore presidency? I went to find out.

I sat uncomfortably in the back row of the hearing, an anonymous 30-year-old in a cheap suit. McCain and other Senators seated themselves at the elevated horse-shoe dais. McCain opened the hearing. From the start, he carried himself differently than he had on the campaign trail during his failed run for the GOP presidential nomination (he had withdrawn from the race just two months earlier). Here was McCain the legislator, ready to quickly resume his responsibilities in the Senate.

McCain recounted how young activists during the campaign kept asking him what his plan was to deal with climate change. The campaign was over, he said, but the question still resonated.

“I am sorry to say that I do not have a plan

because I do not have, nor do the American

people have, sufficient information and

knowledge. But I do believe that Americans,

and we who are policymakers in all branches

of government, should be concerned about

mounting evidence that indicates that

something is happening”

My jaw dropped.

McCain did something in that hearing, and in more hearings to follow, that is rarely done in Congress on climate change, let alone any environmental issue. He used hearings to gain understanding and educate himself from leading scientists and experts. He wanted to learn, and he was willing to use his hard-earned seniority to set the agenda and help educate and engage his colleagues on both sides of the aisle on climate change.

I recall this nostalgically. The political seas are so rough in Washington today, the fear factor so high, that thoughtful policy discourse is becoming a rare commodity in Congress. But McCain’s beginnings on climate in 2000, and his defiant stance on the Senate floor 17 years later, serve as important reminders of the power of information at the right time in the right hands. Good science and other facts are rarely sufficient, but always necessary, to get the right policy result.

The Tenacious Climate Crusader: 2001-2005

McCain was by no means the first Republican to step forward to lead on climate. Nor was it unusual for McCain to buck his party – he cherished the “maverick” label he already owned at the time, and loved to be the underdog outsider.

McCain’s greatness as a leader on climate change was his tenacity. He was not only willing but also highly effective at taking on congressional leaders who had long suppressed climate change from Congress’ agenda. In 2000, climate change was a dead issue in Congress, lost in a black hole at the bottom of an abyss. That is where the mighty lobbyists of K Street wanted to keep it.

McCain and Lieberman dragged climate change into the light where voters could finally watch their elected officials squirm under the sunshine. Lieberman and McCain labored together to build the theater, but the stage spotlight had room only for one, and that was McCain’s job alone. McCain made headlines. Cameras followed him. And as a member of the party that was in the majority, McCain had political levers that were not available to Lieberman, including chairing the Commerce Committee.

At the height of their insurgency, McCain held the Senate procedurally hostage to force a climate vote in 2003. The drama is laid out in a newly published first-hand account by Tim Profeta, Sen. Lieberman’s indefatigable climate aide and strategist at the time. Majority Leader Frist had a bill mired in Senate procedure, requiring the unanimous support of all 100 Senators in order to get unstuck. That is a vulnerable situation for a Majority Leader, and it left Frist exposed to any one Senator willing to incur his wrath. Of all the Senators, of all the bottled up issues that could have jumped into the spotlight that day, it was John McCain who pounced, and he chose climate change.

Things were moving quickly. As Profeta recalls:

McCain recognized this moment of political

leverage and seized it to advance the 2003

climate change legislation. He and Lieberman

would say no to Frist’s request for unanimous

consent, unless Frist would allow a vote on

their bill…

Within minutes, McCain was on the floor of

the Senate, demanding that his climate bill be

scheduled for a vote before anything could

move forward. His request was granted, and

Sen. Frist promised an up-or-down vote on the

bill before the end of the year.

McCain knew it was unlikely they could win the vote and upend the hold of industry lobbyists arrayed against his efforts, but he explained the significance of forcing the vote:

“We’ve insisted on and secured an agreement

for a vote on the measure, a vote that must

take place in order for constituents to know

where their Senators stand on one of the most

important environmental issues of our time.”

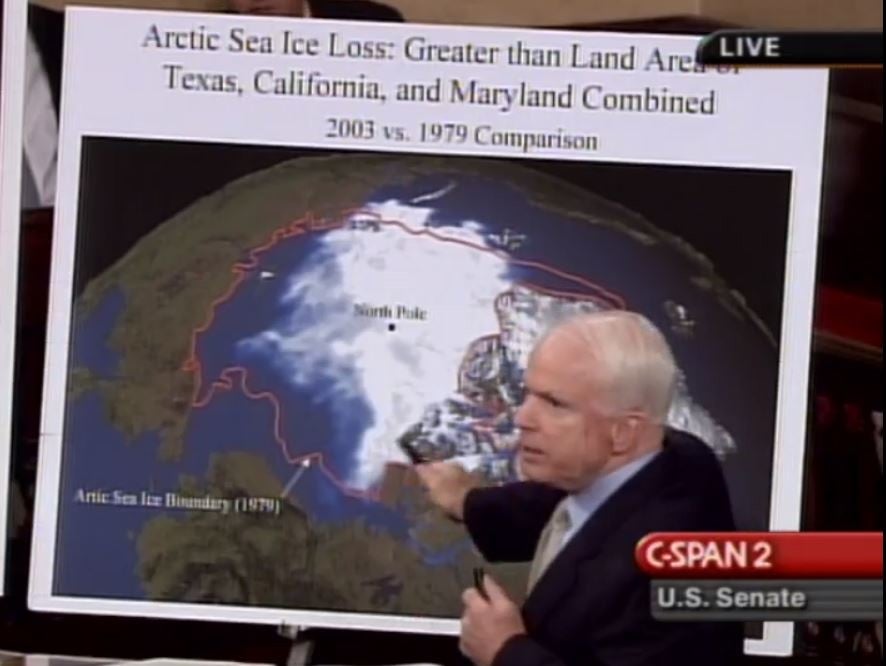

McCain went right after his fellow Senators to apply pressure for the forthcoming vote, as you can see by following the link to this C-Span clip of McCain imploring his colleagues to believe the visual evidence he presented of global warming’s impacts. The legislative staff handling the photo boards is Floyd DesChamps, an important player in McCain’s climate journey, as dedicated to science and facts as his boss, and as dispassionate and even-keeled as his boss was temperamental.

“You can believe me or

your lying eyes.

There are facts that

cannot be refuted by

any special interest

that is weighing in on

this issue more than

any issue since we got

into campaign finance reform.”

(My thanks to Marianne Lavelle for sharing the clip with me after our interview for her recent climate profile on McCain.)

While McCain and Lieberman’s climate bills never passed the senate, their work to force votes and show growing demand for action set the expectation for eventual congressional action and lit the torch that others would pick up and carry. These efforts would peak when the House of Representatives passed the Waxman-Markey American Clean Energy and Security Act in 2009 – the first and last time either branch of Congress took a step toward solving climate change as worthy as the challenge itself. But we are not up to that point of the story yet. Before that, there was a presidential election.

Ready to Act: 2008 and the Campaign for President

In May, 2008, at the height of his presidential campaign, McCain visited a wind energy company in Portland, OR. He was rolling toward his nomination to be the GOP candidate for president. Coming to a state where he was already touting his climate credentials in campaign ads, he delivered a speech devoid of the partisan climate zings delivered by politicians on both sides of the aisle today. Instead, he recommitted to pursuing a cap-and-trade policy and spelled out quantified limits and schedules for reducing pollution. Beyond these technical details, his speech also had lofty eloquence, and recognition of the constant political trials that leading on climate entailed:

“The facts of global warming demand our

urgent attention, especially in Washington.

Good stewardship, prudence, and simple

commonsense demand that we to act meet the

challenge, and act quickly…. global warming

presents a test of foresight, of political

courage, and of the unselfish concern that one

generation owes to the next.”

Some environmentalists, having decided that Obama was the better choice, warned that McCain would not stick to his guns on climate and was already beginning to show the white flag. Al Gore delivered the message in no uncertain terms at the Democrat convention:

“In spite of John McCain’s past record of open-

mindedness on the climate crisis, he has

apparently now allowed his party to browbeat

him into abandoning his support of mandatory caps on global warming

pollution.”

McCain’s record gave little credence to the suggestion that McCain had surrendered to GOP orthodoxy, or even more narrowly to the idea of mandatory caps. He remained committed to cap-and-trade. Gore was pouncing on some verbal jousting McCain had gotten caught up in with the media. Odd as it may seem in hindsight, McCain believed the words “cap and trade” were the magic communications formula for talking about his plan, and he shunned the term “mandatory” whenever journalists tried to get him to use it. During the campaign, he never backtracked from his cap and trade plan’s specific, quantified emissions reduction targets and dates outlined in his May speech.

In all, much of McCain’s political approach on climate in 2008 was pretty similar to Obama’s, John Kerry’s, and Gore’s when they all ran for president: he set the agenda enough to have the room to act when elected; he raised it where it was helpful; but he let political advisers steer how and when to talk about it. Despite the strong climate leadership credentials of all three Democrats, I don’t recall many profiles of courage in terms of their Rust Belt speeches devoted to climate change, either. After all, you can’t save the planet if you don’t first get elected.

We will never know what McCain’s path on climate would have been as President. Would he, like George W. Bush before him, give way to the corporate lobbying powerhouses of K Street and abandon his campaign promises on climate change? The opposition from the business lobby was fierce when Obama took them on, and they certainly wouldn’t have given McCain a pass. And the GOP agenda had unreconciled conflicts between McCain’s climate advocacy and the GOP energy platform he inherited from Bush-Cheney, a platform championed by his running mate, Sarah “Drill Baby Drill” Palin.

But McCain was not Bush, whose one paragraph campaign platform to reduce carbon pollution was a feeble thing compared to McCain’s years of knowledge and work. Importantly, McCain would be getting climate advice from Rick Davis, his campaign manager and closest adviser. Davis was not only concerned himself about climate change, but also had helped McCain turn the erstwhile shunned political topic into a political strength.

What we do know is history: President Obama won, and in the aftermath of Obama’s victory, McCain fulfilled Gore’s unintended prophecy of McCain’s turnabout on climate.

To this day, the prospects of timely and durable US leadership on climate change have never been as high as they were in 2008 when McCain vied with Obama for the mantle of climate leadership.

2009-2010: McCain’s Disappearing Act Begins

After Obama’s election, McCain’s climate journey turned sharply.

In 2009 and 2010, the Senate needed to act. With President Obama’s support, the House passed a major energy and climate bill, which included a cap-and-trade program not unlike the architecture proposed by McCain and Lieberman years before. The bill was more far reaching, however. The details more complex than the incomplete skeleton McCain and Lieberman had started with. At this critical juncture, McCain seized on those differences to criticize the House bill harshly and distance his own prior efforts. He then disappeared on the issue as a bipartisan group of Senators got to work on a climate bill of their own, leaving Republican leadership to his close friend, Lindsey Graham.

Could McCain have boosted momentum for Senate action as other issues began crowding out climate change for the attention of the White House and Senate Leader Harry Reid? Yes, McCain could add a jolt of energy to anything when he was on his game. I would have loved nothing better for him to have tried.

But other obstacles weighed more heavily in sealing the fate of climate legislation in the Senate. Outside Washington, we had failed to build the necessary political support to compel action. Inside Washington, a divided White House ultimately did more damage than good for the Senate negotiations.

During these times, McCain explained to me that he needed to take a back seat on climate because his home politics had changed in Arizona. This is a common reasoning that I’ve heard from Democrats and Republicans, Senators and House members, time and time again on climate and other environmental matters. But I never thought I would hear it from McCain on climate. It still hurts to think about it.

I should not have been surprised. Politicians are always first and foremost political survivors. McCain faced a tough 2010 Tea Party primary challenge after his presidential bid. His home base of support was listening to arguments that he was too moderate and had lost touch with Arizona Republicans. Now he had to go home to Arizona and win a Republican primary for the seat once held by Barry Goldwater. By the end of 2009, polling showed him in a dead heat with his top challenger. McCain campaigned hard. In the end, he defeated his primary opponents, winning 56 percent of the vote.

Like most things in politics, McCain’s decision probably had other drivers as well. He was always more at home being the outsider hammering at the gates. With Obama in the White House and the election wounds still fresh, the idea of working to deliver Obama a key legislative win on climate must not have been very appealing. McCain supporters turn that equation around, noting Obama’s lack of resolve to advance climate legislation ahead of health care, and his proficiency at antagonizing McCain from the get go once in office.

McCain’s backslide on climate sunk to greater depths. In 2010, the Senate voted on whether to revoke the most basic of scientific determinations that climate pollution was a danger to public health and the environment. The “endangerment finding,” as it is known, was an action taken by EPA that opened the doors for the agency to begin regulating climate pollution from industry. McCain had always maintained that it was Congress’ responsibility to act. To him and others, overturning EPA’s accurate scientific verdict on climate change was a chance to stop Obama from going his own way.

Seven years earlier, McCain had bent the Senate to his will, forcing the first climate vote to shine a light on where Senators stood. In June 2010, two months shy of facing his own constituents in the Arizona primary, McCain cast his climate vote on the same side as Jim Inhofe, author of “The Greatest Hoax,” the political bible for climate deniers. Together, they voted to strike down the endangerment finding. Fortunately, they failed, and the finding was preserved.

A Tough But Vital Lesson on Politics and Advocacy

McCain’s 2009 retrenchment on climate hammered home a critically important lesson for me that all climate advocates must heed: never expect any politician to get ahead of their voters, including their primary voters, to do the thing they believe is good policy. This is one of the most basic lessons in Washington – one I had often coached to others learning the ways of DC. Let McCain’s history hammer the lesson home for you as it did me: don’t look for the exceptions. If you do, you miss the point.

McCain set the wrong frame in 2008 when he said climate change was a test of political courage. Waiting for congresses and state houses full of politically courageous, forward thinking, selfless leaders is hallucinogenic recipe for losing. What we need is a congress that sees more political benefit in acting than not acting and fears the risk of doing nothing over the risk of doing something. Until that day happens, little will change.

It is our job on the outside to do the hard work of making sure good policy equates to good politics back home. Asking for courage from members of congress is a recipe for long-term failure. When voter alignment isn’t there, politicians have to choose to either: (A) follow what their voters want and back away until the voters change; or (B) be courageous and retire or be retired (or get lucky). Option B feels great in the near term, but is lousy in the long term. Climate change requires durable, long-term solutions. We have to build for that politically.

It’s a lesson that everyone knows in concept, but it is very resource intensive in practice to implement and achieve. It is not only a question of grassroots power. It is a question of building grassroots political power where we have the least and need the most.

It’s particularly a challenge given the vast resources of those fighting to maintain the status quo. The strategic focus of deep-pocketed donors like the Kochs and Mercers has been to control the Republican party by threatening to defeat lawmakers who cross their agenda, and their top leverage point is GOP primaries.

If nothing else, climate advocates

should heed the lesson of McCain’s

mercurial journey on climate by asking

ourselves: what can we do to align good

climate policies with good politics for

elected officials everywhere, federal

and state, Democrat and Republican?

Advocates who shun Republican primary voters as a lost cause can’t reasonably expect Republican elected officials to find a path back to leadership on the issue. That’s a losing long-term strategy. Our energy and infrastructure systems need stable signals toward cleaner energy sources. Yet our political systems swing between parties from election cycle to cycle. We need to challenge both parties to go further, faster on climate change.

The same resolve is needed at the state level as it is nationally. Eighty-seven percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from states that have split party or full Republican control of state government.

2017: McCain’s Final Climate Punch

At the Environmental Defense Fund, we were working feverishly to secure a win on that climate vote in May 2017. I was at dinner just days before when EDF President Fred Krupp returned from a phone call and told me, “McCain is with us.” Few had worked longer or more effectively with McCain on climate over the years than Krupp, who first educated McCain on cap-and-trade solutions to climate many years prior, near the start of McCain’s climate journey.

It was a stunning development. Two other Republicans were already locked in, including, notably, Graham, McCain’s close friend and the recipient of McCain’s climate baton. We were within shot of the narrowest of victories.

But as important, John McCain was fulfilling a promise he had made to me in his Senate office seemingly a lifetime ago as he faded from climate after the 2008 elections:

“I can’t do this now, but I will be back.”

Having learned my lesson, the proof would be the votes from here on out. For years, they weren’t there. In 2017, McCain had an opportunity to make a difference. Krupp was relentlessly determined to win the methane vote. He got the facts to McCain. McCain delivered.

Later that spring day in 2017, Environmental Defense Fund hosted a reception on Capitol Hill. McCain stopped by to thank us for protecting “our planet, our lives, our children, our grandchildren.” He then shared that he had, a few years prior, revisited Svalbord, Norway, the site of a glacier he had visited many years prior with Hillary Clinton. He had cited the glacier’s alarming retreat as evidence of global warming in his big 2008 climate speech. Now, he said remorsefully:

“It’s gone. It’s gone. It’s a graphic

demonstration of many of the things that are

happening.”

For me, the years slipped back in time. Where have you been John McCain?

And then, like a switch, we were back in 2017. Nuclear power. Nuclear aircraft carriers. McCain had moved on. The moment was gone.

But he had delivered the vote. Was McCain back in the arena for good, ready to throw punch after punch? We’ll never know. But his final climate punch was McCain Classic – the original formula.

Behind Him Others Followed

I conclude with great admiration and appreciation for McCain the fighter; for the combatant who put climate on the congressional agenda in a politically actionable way. I also conclude with regret for not knowing what could have been if he had fought on when he chose not to.

There are some criticisms of McCain that fall flat on my ears. One is that Congress’ failure to act is, as Roberts suggests, proof of McCain’s failings. That is a harsh standard. It is beyond question that choices matter, and accountability for any elected official is a must. However, condemning any single person for Congress’ failure to act on climate change condemns every single person for Congress’ failure to act on climate change.

Thirty years have passed since Jim Hansen testified to the stark realities we now face today, and for 30 years Congress has done nothing significant. That legacy is owned by all members of Congress, all who pay and are paid to thwart progress, all voters who continue to allow this nonsense to transpire, and yes, all climate advocates, because we have not yet succeeded. The only escape from that legacy is to change the future.

Similarly, others assume that McCain should be held to a higher standard. By virtue of having once led, he should therefore be judged more harshly for having fallen back in line. Certainly, his leadership only added to my disappointment when McCain’s stepped back. But consistency as a virtue? Consistency will not deliver us from the perils of climate destruction. The battle before us is a battle for change, exhausting battles against forces that resist and push back at every step.

For whatever McCain lacked in consistency over decades, he had absolutely no problem being stubborn in the moment, unwilling to back down once his back was up. To the contrary, being stubborn was one of McCain’s great assets on climate.

That is how I will always remember John McCain. Railing against the influence of lobbyists, commanding the media’s attention, and daring his colleagues not to hide the truth from their lying eyes. For a while at least, McCain was not only a climate warrior, but the greatest of warriors.

Behind McCain others followed. Of those followers, some to this day hold the memory and lessons of his tenacious leadership, his search for the truth, and the hard realities of politics, and we do the best we can to bring every ounce of energy to the fight ahead.

This is the real and undeniable climate

legacy of John McCain: the torches he

passed, the seeds he planted, the people

he led, the public he awoke. Their story

is not yet complete.

McCain’s climate legacy is not finished, even at his passing. If in the years ahead we as a nation were to fail to rescue our climate future from the perilous fate we find ourselves today, then McCain, like the rest of us, deserve to be judged critically.

I myself am too hopelessly stubborn and optimistic, however, to accept the possibility of that future. When we instead succeed and overcome decades of resistance by special interests. When we faithfully protect our planet, our lives, our children, and our grandchildren. When we firmly embrace the unselfish concern that one generation owes the next. When that happens, it will be easier for even McCain’s sharpest critics to look past what troubles them today, and remember the lion when he roared.